“Don’t you love her madly?

Wanna be her daddy?

Don’t ya love her face?

Don’t ya love her as she’s walkin’ out the door

Like she did one thousand times before?”

– Jim Morrison, The Doors

§ § §

Christmas 1986. I’m spending the month in Thailand. The island of Phuket hasn’t been gentrified yet. The streets are still dirt, the food and accommodation choices are still varied and cheap, and the thin sidewalks that hide the sewer system have only just begun to crack.

Christmas 1986. I’m spending the month in Thailand. The island of Phuket hasn’t been gentrified yet. The streets are still dirt, the food and accommodation choices are still varied and cheap, and the thin sidewalks that hide the sewer system have only just begun to crack.

Then there’s the music. Massive ‘Voice of the Theatre’ speakers blasting out a Sixties vibe from one end of Patong Beach to the other. As a friend of mine who had visited many times said before I jumped on the plane, “I hope you like The Doors.” I LOVE The Doors – still do. But I didn’t understand his comment until I arrived.

More than a few American Vietnam War veterans had settled in their former battle-weary R&R country once hostilities ended. Farangs (non-Thais) can’t own businesses, but they can run them. They can’t own property, but they can lease long-term. And so, the expats on Phuket built shacks on the beach, installed bars and stools, brought in cases of beer and liquor, and then put their real money into stereo systems. This is where Classic Rock came to retire.

R&R country once hostilities ended. Farangs (non-Thais) can’t own businesses, but they can run them. They can’t own property, but they can lease long-term. And so, the expats on Phuket built shacks on the beach, installed bars and stools, brought in cases of beer and liquor, and then put their real money into stereo systems. This is where Classic Rock came to retire.

I asked William, one of the bar owners I became friendly with, why they played The Doors so much – likely fifty percent of the music heard all over the small town. He started telling me stories about being in the war and what The Doors music had meant – still meant – to him and his fellow GIs. “It was the music of the downtime and the music of the battles. It was continuity,” he said. “It was cold beer and warm joints. Jim Morrison was our soundtrack, man.”

The music of The Doors punctuated several weeks-worth of his stories. For a few months in ’68, William had been assigned to a large cavalry camp where they didn’t play reveille at daybreak; they played “Break On Through.” After a particularly bloody firefight near the DMZ a year later, his platoon was attacked, and one of his buddies had been killed. As a tribute, they took the ghetto-blaster he always brought into battle, set it up on a still-smoking tree stump, and pushed ‘play.’ Then they all moved on to their next coordinates. The music, an 8-track of The Doors debut album, played on until the batteries died. William told me that story was so ubiquitous he was convinced Francis Coppola had adapted it to “Ride of The Valkyries” accompanying the infamous airstrike in “Apocalypse Now,” and the use of The Doors’ song “The End” during the opening scene.

The music of The Doors punctuated several weeks-worth of his stories. For a few months in ’68, William had been assigned to a large cavalry camp where they didn’t play reveille at daybreak; they played “Break On Through.” After a particularly bloody firefight near the DMZ a year later, his platoon was attacked, and one of his buddies had been killed. As a tribute, they took the ghetto-blaster he always brought into battle, set it up on a still-smoking tree stump, and pushed ‘play.’ Then they all moved on to their next coordinates. The music, an 8-track of The Doors debut album, played on until the batteries died. William told me that story was so ubiquitous he was convinced Francis Coppola had adapted it to “Ride of The Valkyries” accompanying the infamous airstrike in “Apocalypse Now,” and the use of The Doors’ song “The End” during the opening scene.

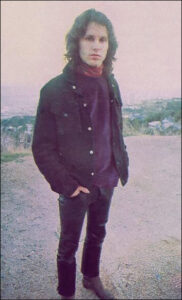

It’s a matter of historical fact: stories about The Doors are really stories about Jim Morrison, the two are joined at the hip. But before there was ‘hip’ – before Manzarek and Krieger and Densmore and Morrison opened their ‘doors of perception’ – there was Jim the beach bum, Jim the poet, and Jim the friend.

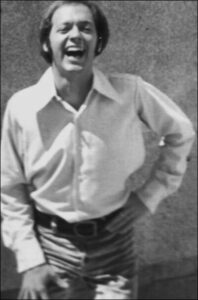

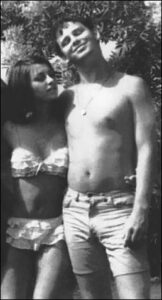

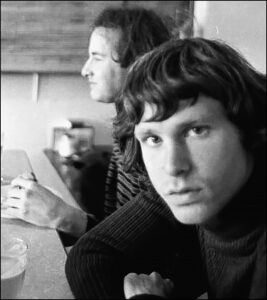

Author Bill Cosgrave (top and right photo) writes about all three in his memoir, “Love Her Madly: Jim Morrison, Mary, and Me.” It’s Bill’s story, but so much more than that.

Author Bill Cosgrave (top and right photo) writes about all three in his memoir, “Love Her Madly: Jim Morrison, Mary, and Me.” It’s Bill’s story, but so much more than that.

In 1963, a sixteen-year-old Billy left his native Toronto and headed south to Florida to spend some time with family friends. It was a largely uneventful visit, but one that introduced him to Mary Werbelow and her boyfriend, Jim Morrison. Billy didn’t know it yet, but their lives would become intertwined with his for years to come.

Two years later, Billy was kicked out of Loyola College in Montreal due to ‘irreconcilable differences’ with the Dean. “What now…?,” he thought. A letter from Mary arrived.

She and Jim had moved to Southern California and were living together – Jim was studying film at UCLA, and Mary had a job there. “There is so much going on here,” Mary said, “The beach is amazing… the weather is perfect… why don’t you come out… you’ll love it.” By rail and by thumb, Billy left Quebec, traveled to L.A., and crashed on their couch.

She and Jim had moved to Southern California and were living together – Jim was studying film at UCLA, and Mary had a job there. “There is so much going on here,” Mary said, “The beach is amazing… the weather is perfect… why don’t you come out… you’ll love it.” By rail and by thumb, Billy left Quebec, traveled to L.A., and crashed on their couch.

The mid-sixties were ground zero for the counterculture. There was a war, a generation gap, segregation, political unrest, long hair, and mass protests to address it all. Timothy Leary’s newly minted phrase, “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out” played like a mantra to the disaffected youth of the day, and Billy, Jim, and Mary were disciples.

Billy’s friendship with Jim blossomed. They spent days and more than a few hazy nights toking on the beach in Venice, talking philosophy and history, and trying to make sense of their present and their future.

Billy loved Jim’s insightfulness, his intelligence, his abstract ideas of life and love, his grasp of concepts both radical and simple, thoughts that found their way into Jim’s poetry. Poetry that would, in the not too distant future, become lyrics put to music that would exhilarate fans all over the world. Those words became the bedrock of over 100 million records sold worldwide.

Jim loved Billy’s compassion, his adventurous nature, and his wild stories. Like the night he crashed the Academy Awards, or got picked up hitchhiking by a van filled with black men who spirited him off to an impromptu vodka-laced house party in South Central Los Angeles… a white kid in the midst of the Watts riots! Jim was bowled over by Billy’s new-found knowledge of the culture and geography of Hollywood, experienced while rubbing shoulders with Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra during rehearsals of TV’s “The Hollywood Palace.” And then there was the time he barely escaped with his pants from an awkward ‘invitation’ within the confines of a Beverly Hills mansion. All of it a world away from the calm, quiet, warm confines of Venice Beach.

And always – always – there was Mary, a woman Billy refers to as his ‘dream girl.’ She was the reason he was in L.A., the reason he had met Jim Morrison, and the reason he had become close friends with both. That Billy loved Mary is unequivocal, but Jim and Mary were drifting apart, and Billy was heartbroken at the sight and the realization he could do nothing about it.

And always – always – there was Mary, a woman Billy refers to as his ‘dream girl.’ She was the reason he was in L.A., the reason he had met Jim Morrison, and the reason he had become close friends with both. That Billy loved Mary is unequivocal, but Jim and Mary were drifting apart, and Billy was heartbroken at the sight and the realization he could do nothing about it.

Mary had taken a job as a go-go dancer at a trendy Sunset Boulevard club. It paid well, the tips were great, and above all, she liked it. Jim didn’t. And he wasn’t working. There was more to it, but that was the weed in their bed of roses.

Billy had a job as a telemarketer for the L.A. Times newspaper. It didn’t pay much, but those meager dollars, combined with calling in a few loans he’d lent out, helped. But then he was broke, and Mary and Jim split, even as they kept trying to make their relationship work. In the end, Billy was left to his own devices. He continued to hang out with Jim off and on, sometimes joining him on Venice’s rooftops under the night sky when Mary kicked him out. A different reality for Billy began to take shape. Jim and Mary dropped Billy off at the Greyhound Bus station, said their goodbyes, and their friend Billy found his way back to Canada.

Two years later, Billy had settled in, maybe even down. He was living in Calgary, and as he writes in the book, “I have a salary, an apartment, a car, and I’m also in love.” Times have clearly changed. Until one day walking along a downtown mall Billy sees someone he once knew staring out at him from a magazine kiosk. It was the face of a bona fide rock star named Jim Morrison!

Two years later, Billy had settled in, maybe even down. He was living in Calgary, and as he writes in the book, “I have a salary, an apartment, a car, and I’m also in love.” Times have clearly changed. Until one day walking along a downtown mall Billy sees someone he once knew staring out at him from a magazine kiosk. It was the face of a bona fide rock star named Jim Morrison!

A fevered phone call to The Doors’ record label in L.A., and in a few moments, the lead singer of the hottest rock band in the world is on the line. “Hey, man, where the fuck are you!” the rock star asked.

Lots of back and forth and catching up as old friends do. At one point, Jim offers Billy a job with The Doors as their Travel Manager, but Billy is ambivalent. He turns it down. Jim’s upset with his decision, but has a consolation prize. The Doors will be playing at the ‘Rock ‘n Roll Revival’ festival in Toronto with John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Alice Cooper, and Chuck Berry, and Jim sets aside tickets for Billy so he can come. Billy makes plans, and they’re both excited to reconnect.

They don’t. Billy tried to contact Jim at the hotel after the concert, but Jim is on the edge of incoherence when he finally does. Drugs, booze, or a combination, Jim can barely put a sentence together. What he does manage to communicate to Billy is the last known whereabouts of Mary. “Try India,” was all he said.

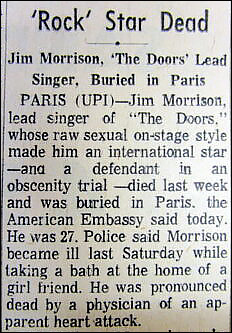

That was the last time Billy spoke with Jim. In 1971, Jim Morrison would be found unresponsive in an apartment bathtub in Paris. He was 27-years-old when he died.

That was the last time Billy spoke with Jim. In 1971, Jim Morrison would be found unresponsive in an apartment bathtub in Paris. He was 27-years-old when he died.

And there Billy’s story might have ended, but Billy never gave up on trying to find Mary. The final four chapters of the book chronicle his successful search for the Mary of his dreams.

‘Love Her Madly’ reads like an acid-fueled road trip. The book is written in two voices. The first two-thirds are penned almost as a prose poem, a style more redolent of Allen Ginsberg and Thomas Pynchon than, say, Jack Kerouac and Ken Kesey.

The last third are the words of a confident writer, someone who’s lived through the eye of a hazy hurricane and emerged buffeted and battled, but better for the journey.

This is a memoir, yes, but could easily pass for a biography of the ‘Lizard King’ himself. We learn as much about Jim as we do Billy.

As I read the book, an Allen Ginsberg quote kept reoccurring in my head that could easily be attributable to the life of either Jim or Billy:

“Follow your inner moonlight; don’t hide the madness.”

What a long strange trip indeed.

Love Her Madly: Jim Morrison, Mary, and Me

A Memoir

Author: Bill Cosgrove

Dundurn Press, 2020

ISBN: 9781459746602

§ § §

This book review first appeared in The British Columbia Review #950 – October 23, 2020

No Comments